Studying millennial students' digital knowledge in the classroom

Published March 23, 2018

Millennials grew up with technology. They understand how to use technology in the classroom. They're digital natives.

The assumption of digital literacy among millennials is widely accepted, not only by the digital natives themselves (Prenksy), but also by older generations (Shiang-Kwei Wang). This belief is perpetuated by confidence many millennials demonstrate when using certain mobile apps, the use of which many exhibit significant expertise. The scene of a grandparent asking a grandchild how to an iPhone or Facebook is nearly a cliché.

But for all of their love of technology, do millennial and Gen Z students really know how to use these resources for academic or business purposes?

This widespread perception of millennial digital literacy has very real consequences. Many universities, under pressure to reduce credit requirements for bachelor degrees and increase five-year graduation rates, have reduced or eliminated computer class requirements from curricula. Community college transfer (feeder) degrees often follow suit, as administrators attempt to ensure direct alignment with target universities. Decision makers often cite high school computer class experience as sufficient to ensure digital competency. Of course, this same rationale could be used to eliminate English and mathematics classes as these courses are also taught in high schools. The need to verify a baseline competency in English and mathematics among college graduates is unquestioned. However, despite resounding evidence that a lack of computer competence is a major issue for employers, it is interesting to note that many institutions do question the need to determine a baseline competency in digital literacy.

Many studies indicate that the assumptions regarding millennials' computing knowledge are unfounded (Kirschner and De Bruyckere). Major questions include how students use technology, and whether a culture of use and ownership match the attributes often ascribed to them as digital natives. Educators should not make assumptions about students' ability to use technology in this context if their culture of use is based on prior experiences dominated by leisure and entertainment (Gulatee). Studies indicate that millennials tend to be "flickers and bouncers;" they use the Internet for research in short bursts, rather than sustained reading and study. A primary use of digital technology is for communication with other millennials (Shiang-Kwei Wang). This experience and expertise with multiple social media platforms is not necessarily an indicator of significant digital literacy, particularly regarding competency with productivity software or even basic keyboarding skills.

Studying Digital Literacy in Incoming Freshman

We, Casey Wilhelm and Ted Tedmon, decided to attempt to measure digital literacy among incoming college freshmen, a large majority of whom are digital natives, and compare their capabilities to those of faculty members. In our study, faculty members averaged 28.8 years older than the freshmen (20.1 vs. 48.9 years of age). The study asked all participants to self-assess their digital competency levels prior to taking a summative assessment. Our study took place at two separate colleges, Norther Idaho College and College of Southern Nevada, with significantly different demographics. Fundamentally, we wanted to see if college administrators were justified in making the assumption that students today are, in fact, digitally literate and that courses that teach computing fundamentals are unnecessary.

The evaluation used Survey Monkey for the self-assessment and McGraw-Hill's SIMnet, which measured digital literacy in a simulated environment, for the summative assessment (please see Appendix A for question samples). The SIMnet evaluation was comprised of 50 questions and students were given 50 minutes to complete the exam. A typing test, comprised of a 3-minute warm-up and a 5-minute assessment, was also administered to each participant. While this study was hardly scientific, (lacked control groups, etc.) its relatively large sample size of 213 freshmen and 23 faculty members do lend it some credibility.

The Results:

- Self-Assessment & Keyboarding - The scores were consistent across both colleges. Incoming freshmen (self-assessed higher than faculty in all areas, except for keyboarding. In keyboarding, freshmen self-assessed at 32.8 WPM while faculty self-assessed at 43.8 WPM. The actual keyboarding speed was 21.2 for freshmen and 39.8 for faculty. While both groups self-assessed higher than the actual tested speed, faculty were much more accurate in their self-assessment as well as significantly faster.

- Computer Knowledge - Regarding computer knowledge, students self-assessed higher than faculty in all areas with the closest being spreadsheet capability (freshmen - 6.6; faculty 6.2), and computer software knowledge being the furthest (freshmen - 7.7; faculty 5.3).

- Summative Assessment Results - In the summative assessment of computer knowledge as measured using McGraw-Hill's SIMnet, students scored lower than faculty in every category with an overall average score difference of 32.1% (freshmen 36.8%; faculty 68.9%).

Conclusions:

This study indicates that millennials are very confident in their technical knowledge and capability, but this confidence may be misplaced. Faculty members, supposed non-digital natives, seemed less confident of their computer literacy yet demonstrated considerably higher levels of technical capability than millennials. These results were consistent with many other studies that indicate that increased knowledge allows individuals to more accurately judge their limitations. (Dunning) While additional, more controlled studies are required, this study indicated that digital natives are not nearly as computer literate or classroom proficient as they think they are; nor are they as capable as many university administrations may believe. If true, this has significant implications regarding freshmen enrollment in classes, such as fully-online classes, which require significant levels of digital literacy to succeed. This disparity between perceived capability and actual capability could impact performance and retention in these classes.

Works Cited

- Dunning, Justin Kruger and David. "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1999): 1121-1134.

- Gulatee, Yuwanuch and Combes, Barbara. "Owning ICT: Student Use and Ownership of Technology." Walailak Journal of Science & Technology (2018): 81-94.

- Kirschner, Paul and Pedro De Bruyckere. "The myths of the digital native and the multitasker." Teaching & Teacher Education (2017): 135-142.

- Prenksy, M. "Digital natives, digital immigrants." On the Horizon (2001): 9(5), 1-6.

- Shiang-Kwei Wang, Hui-Yin Hsu, Todd Campbell, Daniel C. Coster, max Longhurst. "An investigation of middle school science teachers and students use of technology inside and outside the classrooms: considering whether digital natives are more technology savvy than their teachers." Association for Educational Communications and Technology (2014): 637-662.

Appendix A:

Sample self-assessment questions:

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very knowledgeable and 10 being extremely knowledgeable, how would you rate your knowledge of computer hardware?

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very knowledgeable and 10 being extremely knowledgeable, how would you rate your knowledge of computer software?

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very knowledgeable and 10 being extremely knowledgeable, how would you rate your knowledge of computer networks

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very knowledgeable and 10 being extremely knowledgeable, how would you rate your knowledge of file management?

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very capable and 10 being extremely capable, how would you rate your ability to use word processing software such Microsoft Word or Google Docs?

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very capable and 10 being extremely capable, how would you rate your ability to use spreadsheets such Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets?

- On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not very capable and 10 being extremely capable, how would you rate your ability to use presentation software such Microsoft PowerPoint or Google Slides?

- Approximately how many words per minute can you type?

Sample summative (McGraw-Hill SIMnet) questions:

- Hardware terminology, for example: As the main processor of a computer, the ___ is responsible for organizing and carrying out instructions in order to produce a desired output. Select your answer:

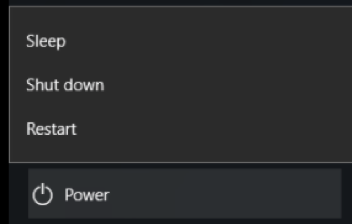

- System software, for example: Which command should you use if you want to power down the computer but not close any open apps?

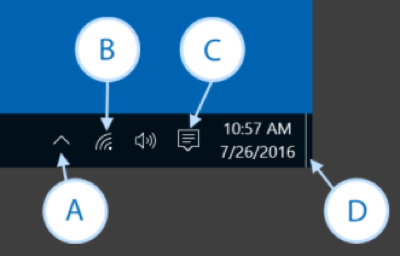

- Networking, for example: Which icon do you click to connect to a wireless network?

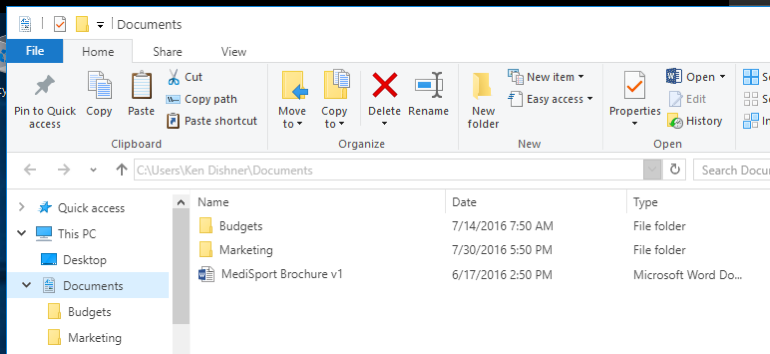

- File management, for example: Copy the MediSport Brochure v1 file into the Marketing folder.

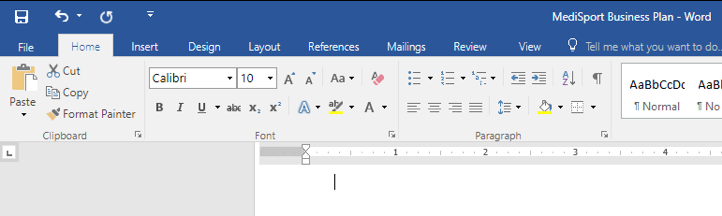

- Use of word processing programs, for example: Add a bibliography using the Bibliography style

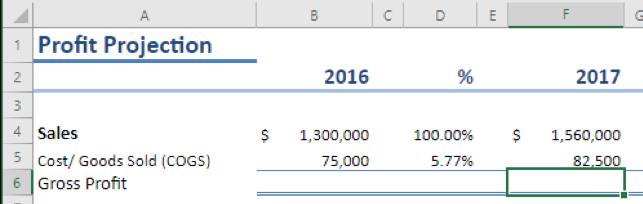

- Use of spreadsheet programs, for example: Enter a formula in the selected cell to calculate the profit projection for 2017: total sales (cell F4) minus the cost of goods sold (cell F5).

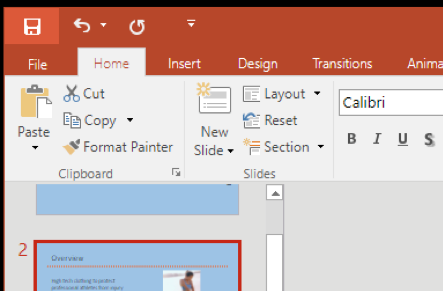

- Use of presentation software, for example: Add a new slide to the presentation that will include only a title for the slide.

a. SSD

b. RAM

c. Chipset

d. CPU

About the Authors

Casey Wilhelm - Northern Idaho College

Casey Wilhelm teaches digital literacy for business, computer systems and business applications, introduction to business and principles of marketing at North Idaho College. His research interests are adult learning, instructional design in digital environments, and cognitive information processing. Casey has various degrees including an M.B.A., M.I.T., M.S. in Adult and Organizational Learning and a M.Ed. in Instructional Design and Technology. Before working in higher education, he held management positions in the insurance and wine/hospitality industry.

Ted Tedmon - Northern Idaho College

Ted Tedmon teaches management, business principles, and digital literacy courses at North Idaho College in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. His primary research interests include andragogy, instructional design, and memory formation. Ted studied Strategic Policy and Planning at the Naval War College as well as Management at Troy University. Prior to joining North Idaho College Ted served as Commander of the US Navy's largest Airwing during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. As a Captain with over 26 years of service and over 6,000 flight hours, he earned the Legion-of-Merit, 4 Meritorious Service Medals, and numerous other decorations. In his free time Ted works with survivors of domestic violence and serves on the board of directors of the Coeur d'Alene Women's Center.