How to Build a Learner-Centered Syllabus

The syllabus is a guide of expectations and policies for students and instructors to be on the same page. Take yours to the next level by making it learner-centered.

I have a love/hate relationship with my syllabus. Facebook would call our status “complicated.”

I love the idea of a simple document that contains all the most important details of my class; an organized source of information for everything from learning objectives to late policies. What format is the exam? It’s in the syllabus. When are the professor’s office hours? Syllabus. So easy.

In practice, however, the syllabus is often anything but simple.

First, the students don’t often read the full document. Even when they do, many times they are trying to find the one loophole that allows them to do something you hadn’t anticipated (thereby making your syllabus longer next semester). Speaking of length, the “one-page” camp is constantly at war with the “everything but the kitchen sink” faction, with most of us caught in the middle. Too long and it’s unreadable; too short and it’s incomplete.

As if this wasn’t already enough to consider, we’re then told that the syllabus forms an important first impression and should reflect our “teaching personality.” However, it is also a legally binding contract, and many colleges and universities dictate sections that must be included (some even require standardization down to the very formatting).

So, there seems to be a lot riding on our syllabi. Where can we start?

One suggestion is to begin by moving toward a learner-centered syllabus, which has several distinct features:

- Emphasis on course objectives and provide a rationale for how specific assignments support these objectives.

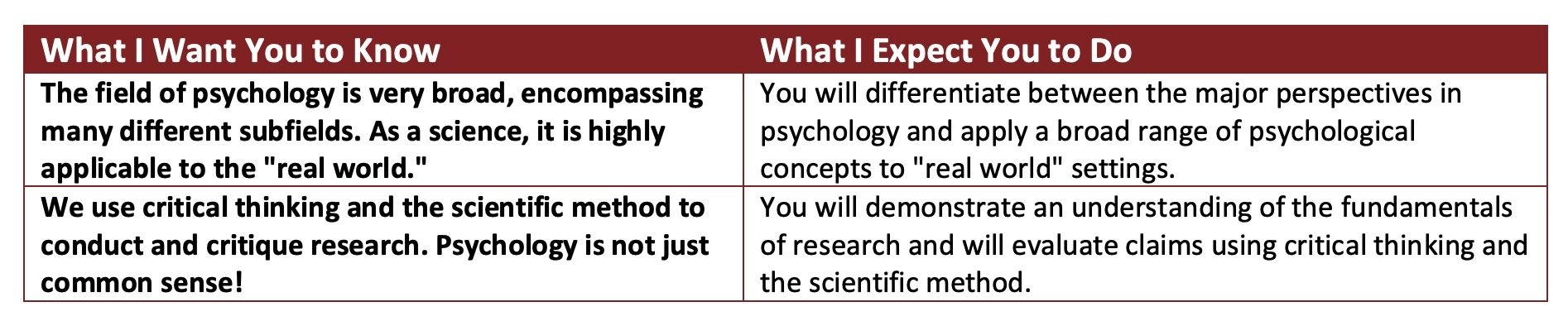

- First, think about what you really want students to know by the time they leave your class, and then communicate those expectations to the students in the form of learning objectives. For example, my Introductory Psychology syllabus learning objectives include both “what I want you to know” and “what I expect you to be able to do” sections (example of my first two learning objectives below).

- Second, tie each topic and assignment to the learning objective(s) it supports. This will help students see that they aren’t doing “busy work” for no reason. You can do this by reinforcing the learning objective when a new chapter, assignment, etc. is introduced (see example below), or by organizing each content area and assignment according to the corresponding learning objective. For example:

- First, think about what you really want students to know by the time they leave your class, and then communicate those expectations to the students in the form of learning objectives. For example, my Introductory Psychology syllabus learning objectives include both “what I want you to know” and “what I expect you to be able to do” sections (example of my first two learning objectives below).

- Changes the language away from a list of requirements and expectations to offering guidance and strategies for success.

- Try including a section on your teaching philosophy – Do you want to emphasize learning instead of grading? Do you strive to create a learning environment where all students are valued and included? Make your philosophy clear and give students a chance to see what’s most important to you.

- Emphasize that students aren’t expected to know everything (that’s why they’re students!) and give advice for how to maximize their experience in the course. Make sure they know their resources and how to ask for help when needed.

- Provides opportunities for feedback and shared governance.

As much as is possible and practical in your course, allow students to have some freedom in deciding their own policies. This ownership can dramatically improve student buy-in. This can be something as simple as offering 12 homework assignments but only counting 10, or having students vote on the electronics policy for the classroom.

Now that you’ve thought about reframing the tone of the syllabus, what about more practical concerns like style and length?

Everyone is different (and requirements vary greatly from institution to institution), but here are some easy-to-implement tips:

- Let your LMS do the heavy lifting. In other words, try keeping two copies of your syllabus – a document version that you can send out via email, print, and hand out in class, etc., and another more complete version that lives in your LMS. The full version can include all the long policy explanations, required statements, and assignment details that aren’t needed in the brief document.

- Let your syllabus show your personality! Try using templates for newsletters that can be found in most word-processing apps. These can add color and flair to an otherwise boring syllabus without requiring much work on your part. Adding visual interest with a few personalized pictures (an image of you teaching, your classroom or university office, etc.) will give students more familiarity with you. Also, don’t underestimate the value of a good cartoon or meme!

- Make an early first impression. Try sending out your syllabus to all registered students via email in advance of classes starting. This will give them time to read and get excited for the new semester, as well as get a jump on asking questions, gathering supplies, and registering for tech resources you might require.

- Don’t re-invent the wheel! Look for syllabi in your area that capture the look and feel you’re trying to achieve and ask the instructor(s) to share. Most teaching-centered colleagues are eager and willing to help. There are also online resources that are designed to give you a starting point; some even provide data to demonstrate the effectiveness of their syllabi!

In my area, for example, the Society for the Teaching of Psychology (APA Division 2) offers Project Syllabi, a collaborative effort to provide peer-reviewed syllabi for a number of psychology classes. Syllabi can be downloaded, reviewed, and adapted to your own courses. Project Syllabi also provides resources on writing excellent syllabi that are applicable to everyone regardless of discipline. - Solicit advice from the front-line experts: your students! Ask for feedback toward the middle of the semester (and maybe again at the end) about what you are doing well and what you could improve.

You can ask questions like:- What was your first impression of me (and of this class) when you read the syllabus?

- What did you find confusing?

- What did you find interesting?

- What were you most looking forward to, and what were you dreading?

- Is there anything you would add/remove/rewrite based on your experiences?

- Is there anything I can change that would have improved your understanding of this class?

In addition to looking at examples from your content area, many college and university teaching centers offer help with syllabus creation and revision. If you don’t already know the people in your center for teaching and learning (if you’re lucky enough to have one), this is a great way to make new connections!