The Leadership Equation — What it takes to be a successful leader

Early studies were based on two main theories–trait, focusing on qualities of the leader, and behavior, focusing on leadership actions.

What does it take to be a successful leader? Researchers have been trying to answer this question for years. The Encyclopedia of Leadership identifies more than 40 theories or models of leadership1. Early studies were based on two main theories–trait, focusing on qualities of the leader, and behavior, focusing on leadership actions.

Leadership Trait Theory

Sir Francis Galton is credited with being one of the earliest leadership theorists, mentioning the trait approach to leadership for the first time in his book Hereditary Genius, published in 1869. In keeping with the general thinking of the period, Galton believed that leadership qualities were genetic characteristics of a family. Qualities such as courage and wisdom were passed on–from family member to family member, from generation to generation.2

The trait theory of leadership makes the assumption that distinctive physical and psychological characteristics account for leadership effectiveness. Traits such as height, attractiveness, intelligence, self-reliance, and creativity have been studied, and lists abound, from The Leadership Traits of the U.S. Marine Corps to the Leadership Principles of the U.S. Army. Almost always included in these and other lists of important leadership traits are (1) basic intelligence, (2) clear and strong values, and (3) a high level of personal energy.3

Trait Theory Applied

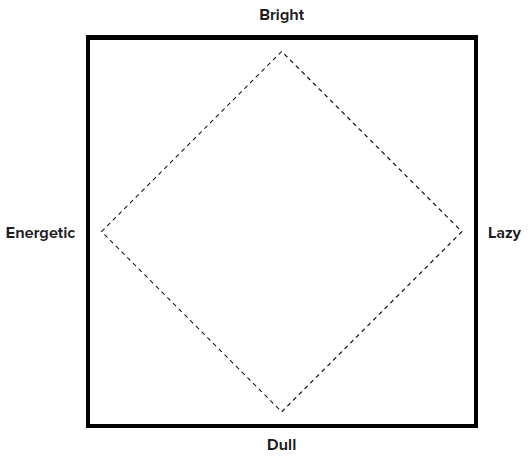

An interesting application of trait theory was practiced by Paul Von Hindenburg, war hero and second president of post-World War I Germany. Von Hindenburg used a form of trait theory for selecting and developing leaders. He believed that leadership ability was determined by two primary qualities – intelligence (bright versus dull) and vitality (energetic versus lazy). He used a box (see the Figure below) to evaluate potential military leaders on these two dimensions.

Dimensions of Leadership

If an individual was deemed to be bright and energetic, he was developed as a field commander, because it takes judgment and gumption to succeed as a leader on the battlefield. If the individual was deemed to be energetic but dull, he was assigned to duty as a frontline soldier where activity was needed but dullness could be tolerated in a non-leadership position. If the individual was believed to be bright but lazy, he was assigned to be a staff officer, because intelligence is important for developing a creative strategy that others may implement. If the individual was judged to be lazy and dull, he was left alone to find his own level of effectiveness.4

Leadership Behavior Theory

During the 1930s, a growing emphasis on behaviorism in psychology moved leadership researchers in the direction of the study of leader behavior versus leadership traits. A classic study of leader behavior was conducted at the University of Iowa by Kurt Lewin and his associates in 1939. These researchers trained graduate assistants in behaviors indicative of three leadership styles: autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire. The autocratic style was characterized by the tight control of group activities and decisions made by the leader. The democratic style emphasized group participation and majority rule. The laissez-faire leadership style involved low levels of any kind of activity by the leader. The results indicated that the democratic style of leadership was more beneficial for group performance than the other styles. The importance of the study was that it emphasized the impact of the behavior of the leader on the performance of followers.5

Behavior Theory Applied

In Shackleton’s Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer, Margot Morrell presents a detailed account of Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition and the leadership lessons to be learned from it. The book is based on primary sources – on the actual comments of the men who were led by Shackleton. She uses diaries, letters, and interviews to understand Shackleton’s leadership behavior. Morrell believes that even today we can look to his behaviors as a source of inspiration and education. Five foundations of Shackleton’s leadership behavior are competence in the task at hand, leading by example, communicating a vision, keeping up morale, and maintaining a positive attitude. Morrell concludes from her research of Shackleton and leadership: “If you look closely at any successful leader, you will find (he or she) is executing on these five points.6

Leadership Contingency Theory

Research shows that both leadership traits and leadership behavior are important for leadership effectiveness, supporting the practice of selecting leaders with an emphasis on traits and training leaders with an emphasis on behavior.7 Both the trait theory and the behavior theory of leadership were attempts to identify the one best leader and the one best style for all situations. By the late 1960s, it had become apparent that there is no such universal answer. Leadership contingency theory holds that the most appropriate leadership qualities and actions vary to some degree from situation to situation. Effectiveness depends on the leader, follower, and situational factors. Forces in the leader include personal values, feelings of security, and confidence in employees. Forces in the follower include knowledge and experience, readiness to assume responsibility, and interest in the task or problem. Forces in the situation include organizational structure, the type of information needed to solve a problem, and the amount of time available to make a decision.8

Matching the Qualities of Leaders, the Characteristics of Followers, and the Nature of the Situation

In the past 60 years, more than 65 classification systems have been developed to define the dimensions of leadership, and more than 15,000 books and articles have been written about the elements that contribute to leadership effectiveness. The usual conclusion is that the answer depends on the leader, follower, and situational variables. A leader in a bank and a leader on the farm will need different knowledge and skills. Experienced followers and new followers will have different leadership needs. Situational factors include the job being performed, the organizational culture, and the urgency of the task.

No single element explains why leadership takes place. Leadership results when the ideas and deeds of the leader match the needs and expectations of the followers in a particular situation. The relationship between General George Patton, the U.S. Third Army, and the demands of World War II resulted in leadership; however, the same General Patton probably would not have much influence on the membership and goals of a parent-teacher organization (PTO) today. Even if there were agreement about goals, disagreement over style probably would interfere with the leadership process.

A modern example of matching the qualities of the leader, the characteristics of followers, and the nature of the situation is Nelson Mandela, the first black president of South Africa.9 A negative example, but one of historic significance, is that of Adolf Hitler, the German people, and the period 1919 to 1945.

Hitler generated his power through the skillful use of suggestion, collective hypnosis, and every kind of subconscious motivation that the crowd was predisposed to unleash. In this way, the people sought out Hitler just as much as Hitler sought them out. Rather than saying that Hitler manipulated the people as an artist molds clay, certain traits in Hitler gave him the opportunity to appeal to the psychological condition of the people. Seen in this light, Hitler was not the great beginner, but merely the executor of the people’s wishes. He was able to understand the character and direction of the people and to make them more conscious of it, thereby generating power that he was able to exploit. This was not due to his personal strength alone. Isolated from his crowd, Hitler would be with reduced potency. Hitler had many personal weaknesses including fundamental moral deficiency, but as one who sensed the character and direction of the group, he became the embodiment of power. No doubt his strength came through his claiming for himself what actually was the condition and achievement of many.10

It is clear that destructive results can be traced to a toxic triangle of leader, follower, and situational factors. Destructive leaders with charisma, narcissism and an ideology of hate can enlist susceptible followers with bad values, unmet needs, and ambition in a conducive situation of instability, perceived opportunity, and lack of checks and control. The outcome can be disastrous.11 Ultimately, the leader, the followers, and the situation must match for either good or bad leadership to take place. One without the other two, and two without the third, will abort the leadership process.12

Hollywood provides an example of matching the qualities of a leader with the characteristics of followers, and the nature of the situation to result in effective leadership for good outcomes. Star Trek Captain James T. Kirk was the quintessential leader of the talented and diverse crew of the Starship Enterprise. He (1) never stopped learning, (2) listened to the advice of people with vastly different opinions, (3) got down in the trenches to understand the needs of his crew, (4) considered the perspective of adversaries, and (5) changed course radically when circumstances dictated. Kirk’s approach to leadership was effective with a unique team that succeeded time and again, regardless of the obstacles faced.13

For related reading, see:

The Leadership Challenge by James Kouzes and Barry Posner (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2017).

The Leader’s Companion by J. Thomas Wren (New York: Free Press, 1995).

1. B. Bass and R. Bass, Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership, 4th ed. (New York: Free Press, 2008); and G. Goethals et al., eds., Encyclopedia of Leadership (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004).

2. F. Galton, Hereditary Genius (Bristol, UK: Thoemmes, 1869).

3. P. Northouse, Leadership, 7th ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015); S. Zaccaro, “Trait-Based Perspectives,” American Psychologist 62 (2007), pp.6-16; and R. Hogan et al., “What Do We Know about Personality: Leadership and Effectiveness,” American Psychologist 49 (1994), pp.493-503.

4. H. Mann, “State of OKI,” Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Planning Conference, Cincinnati, OH, 1998.

5. K. Lewin et al., “Patterns of Aggressive Behavior in Experimentally Created Social Climates,” Journal of Social Psychology 10 (1939), pp. 271-99.

6. M. Morrell, Shackleton’s Way (New York: Viking Press, 2001).

7. A. Kinicki and B. Williams, Management (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013), p.453.

8. F. Fiedler, A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967); E. Hollander, Leadership Dynamics (New York: Free Press, 1978); P. Hersey and K. Blanchard, “Life Cycle Theory of Leadership,” Training and Development Journal 23 (1969), pp.26-34; A. Tannenbaum and W. Schmidt, “How to Choose a Leadership Pattern,” Harvard Business Review 36 (March-April 1958), pp.95-101; R. Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents (New York: McMacmillan,1990); G. Yukl, Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2012); and R. House, “A Path-Goal Theory of Leader Effectiveness,” Administrative Management Quarterly16 (1971).

9. A. Hadland, “Nelson Mandela,” in K. Asmal et al., Nelson Mandela in His Own Words (New York: Little, Brown, 2003).

10. E. Jennings, An Anatomy of Leadership (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972), 13.

11. A. Padilla et al., “The Toxic Triangle,” Leadership Quarterly 18 (2007), pp.176-94, Fig.1.

12. P. Hersey, The Situational Leader (New York: Center for Leadership Studies, 1997); and E. Hollander, Leadership Dynamics.

13. A. Knapp, “Five Leadership Lessons from James T. Kirk,” Forbes (March 5, 2012).