Work Morale: Practical Leadership Tools

Increasing morale at work means that leaders aim to find flow for their employees. The key to understanding flow is finding where challenge and skill meet.

The importance of morale has been recognized by all great leaders. Napoleon once wrote: "An army's success depends on its size, equipment, experience, and morale . . . and morale is worth more than all of the other elements combined."1 Meta-analyses of research studies show positive relationships between employee morale and organizational commitment, job performance, organizational citizenship behavior, and retention.2

Brad Bird, director of award-winning films at Pixar Animation, makes the business case for employee morale: "In my experience, the thing that has the most significant impact on a budget, but never shows up in the budget, is morale. If you have low morale, for every dollar you spend, you get 25 cents of value. If you have high morale, for every dollar you spend, you get $3 dollars of value, not to mention a beautiful product."10

Practical Leadership Tips

The task of leadership is to manage morale, which means making sure people (1) feel they are given the opportunity to do what they do best every day, (2) believe their opinions count, (3) sense their fellow employees are committed to doing high-quality work, and (4) have made a direct connection between their work and the company's mission. By focusing on these key factors and by adhering to the following proven tips for being an effective leader, the leader can keep morale high and performance up in the workgroup or organization.11

- Be predictable. One good rule for leading people is to be consistent. If you give praise for an act today and criticism for the same act tomorrow, the result will be confusion.

- Be understanding. Try to see things from the other person's view. How can you appreciate what another person is going through if you have never been there or at least listened?

- Be enthusiastic. The atmosphere you create determines whether people will give their best efforts when you are not present. Why would they care if you do not?

- Set the example. It is difficult to ask others to do something (for example, be at work on time) if you aren't willing to do it.

- Show support. People want a leader they can trust in times of need and a person they can depend on to represent their interests. Care about your people and they will care about you. Mutual loyalty is an important force for getting things done, especially in emergencies and adverse conditions.

- Get out of the office. Visit front line people, with your eyes and ears open. Ask questions, understand their concerns, and gain their support. This has to be done often enough to show that you care about their problems and their ideas.

- Keep promises. When you make promises, keep them faithfully. One key to being an effective leader is credibility. Credibility is the formation of trust, and trust is an essential quality employees want in a leader.

- Praise generously. Never let an opportunity pass to give a well-deserved compliment. Don't forget to show appreciation for effort as well as accomplishments, and do so in writing whenever possible.

- Hold your fire. Say less than you think. Cultivate a pleasant tone of voice. How you say something is often more important than what you say. Most important, ask people; don’t tell them. Discuss; don't argue.

- Always be fair. Show respect, consideration, and support for all employees equally, but differentiate rewards based on performance. Reward good performers in a similar fashion, and reward non-performers in a similar fashion, but don't reward good performers and non-performers in the same fashion. Doing so is a sure way to de-motivate good performers and lower the quality of work for all.

Psychological Health and the Concept of Flow

Thomas Jefferson believed it was neither wealth nor splendor, but tranquility and occupation, that give happiness.14 Along these lines, University of Chicago psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term flow after studying artists who could spend hour after hour painting and sculpting with enormous concentration. The artists, immersed in a challenging project and exhibiting high levels of skill, worked as if nothing else mattered.15

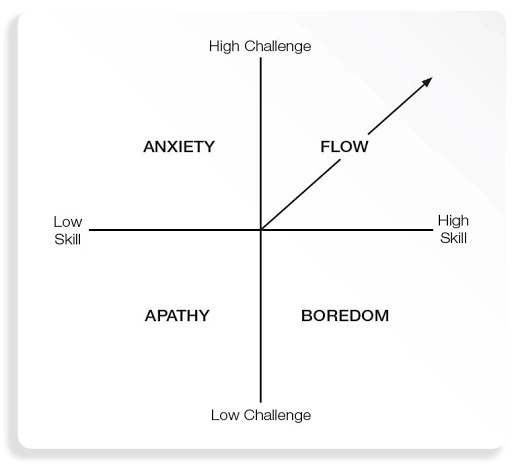

Flow is the confluence of challenge and skill, and it is what the poet Joseph Campbell meant when he said, "Follow your bliss." In all fields of work, from accounting to zoo keeping, when we are challenged by something we are truly good at, we become so absorbed in the flow of the activity that we lose consciousness of self and time. We avoid states of anxiety, boredom, and apathy, and we experience flow. See the Figure below.

The Experience of Flow Combines High Challenge and High Skill

Note:

- Low skill + low challenge = apathy and diminished work-life

- Low skill + high challenge = anxiety and low self-esteem

- High skill + low challenge = boredom and low creativity

- High skill + high challenge = the experience of flow and work fulfillment.

What is it like to be in a state of flow? Csikszentmihalyi, in his book The Evolving Self, reports that over and over again people describe the same dimensions of flow:

- A clear and present purpose distinctly known.

- Immediate feedback on how well one is doing.

- Supreme concentration on the task at hand as other concerns are temporarily suspended.

- A sense of growth and being part of some greater endeavor as ego boundaries are transcended.

- An altered sense of time that usually seems to go faster.16

At this point in time, where are you in your work and professional life: Are you in a state of apathy, anxiety, boredom, or flow? If you are not now in a state of flow, what would it take to get you there? The untapped potential of people is the main message in the concept of flow. Effective leaders will take action to be sure no employee stays long in a state of apathy, anxiety, or boredom but, instead, is challenged to perform in his or her area of strength and to gain the satisfaction of the experience of flow.

1. N. Bonaparte, How to Make War, trans. K. Sanborn, ed. Y. Cloarec (New York: Ediciones la Calarera, 1998), www.napoleonguide.com/maxim_war.html

2. N. Podsakoff et al., "Turnover and Withdrawal Behavior," Journal of Applied Psychology (March 2007), pp. 438-54; B. Hoffman et al., "A Quantitative Review of the OCB Literature," Journal of Applied Psychology (March 2007), pp. 555-66; and T. Judge et al., "The Job Satisfaction-Job Performance Relationship," Journal of Applied Psychology (February 2004), pp. 165-77.

3. H. Rao and R. Sutton, "Innovation Lessons from Pixar," McKinsey Quarterly (April 2008), pp. 1-9.

4. G. Spreitzer and R. Quinn, A Company of Leaders (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001); and W. Adamchik, No Yelling (New York: Firestarter Speaking and Consulting, 2006).

5. J. Meacham, Thomas Jefferson (New York: Random House, 2012).

6. M. Csikszentmihalyi and I. Csikszentmihalyi, Optimal Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

7. M. Csikszentmihalyi, The Evolving Self (New York: HarperCollins, 1994); and M. Csikszentmihalyi, Flow (New York: Harper & Row, 2008).