Servant Leadership: The Philosophy & Practice of Caring Leadership

Servant Leadership begins with the feeling deep down inside that one cares about people and wants to help others. Then conscious choice causes one to aspire to lead.

Management author Robert Greenleaf states that servant leadership is a calling to serve. This calling begins with the feeling deep down inside that one cares about people and wants to help others. Then conscious choice causes one to aspire to lead. The great leader is a servant first, and that is the secret of his or her greatness.

The servant-leader is different from the individual who is motivated by selfish goals. Winston Churchill captured the spirit of servant leadership when he said, “We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give. What is the use of living if not to strive for noble causes and to make this muddled world a better place for those who will live in it after we are gone?”

People do not trust the self-server, whose primary thoughts are for personal gain. Trust is given to the leader who works for the common good and has the interests of others at heart. The servant-leader is the one people will choose to follow, the one with whom they will prefer to work.

Greenleaf coined the term servant leadership after reading The Journey to the East, by Herrmann Hesse. In this story, Leo, a cheerful and caring servant, supports a group of travelers on a long and difficult journey. His helpful ways keep the group's morale high and purpose clear. Years later, the storyteller comes upon a spiritual order and discovers that Leo is the group's highly respected leader. By serving the travelers unselfishly rather than trying to lead them for personal gain or prestige, Leo had helped ensure their survival and eventual success. This story represented a transformation in the meaning of leadership for Greenleaf. Servant leadership is not about personal ego or material rewards. It is about a true motivation to serve the interests of others. Greenleaf founded a nonprofit organization called the Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership, formally called the Center for Applied Ethics, to foster leadership focused on service to others.

A sure sign of servant leadership is the leader who stays in touch with the challenges and problems of others. The leader's helpful ways keep morale and performance high. One good way to do this is to get out of the executive suite and onto the shop floor, out of headquarters and into the field, out of the ivory tower and into the real world. A popular term used to describe this is managing by walking around (MBWA).

One company has an active reception area: pickup, delivery, walk-in customers, and in-coming calls. To give receptionists a little relief, and to stay in touch with real customers, real employees, real products, and real problems, each top executive is on a duty roster giving two hours a month at the reception desk... including the president.

Servant leaders do not view leadership as a position of power; rather, they are coaches, stewards, and facilitators. They seek to create conditions where others can fulfill their potential and do great work. Their approach is to ask, How can I help?

Quint Studer, the author of Hardwiring Excellence, identifies four questions servant leaders should ask all employees:

- What is going right?

- What can be improved?

- Do you have what you need?

- How can I help you achieve your goals? In addition, new employees should be asked:

- How has your experience been compared to what you thought it would be?

- What has worked well? What has not worked well?

- You have a fresh pair of eyes. What ideas and suggestions do you recommend?

Google launched project OXYGEN to identify the most effective behaviors of managers inside the organization. The three most important behaviors reflect the spirit and practice of servant leadership: being available by meeting regularly with employees, communicating by asking questions rather than always providing answers, and showing support by taking an interest in employees personally.

Access, Communication, and Support

The servant-leader is committed to people, and this commitment is shown through access, communication, and support:

- Access (being available). People need to have access to their leaders, to be able to read their faces, to see recognition of their own existence reflected in their leaders' eyes. Management by objectives and other rational techniques of management do not alter fundamental human needs. People need contact and support, and effective leaders at all levels of responsibility recognize this as one of their primary tasks. The age of computers, information technology, e-mail, and social media does not change the importance of the human moment at work.

- Communication (listening effectively). The effective leader knows the value of communication. As long ago as 59 bc, Julius Caesar kept people up-to-date with handwritten sheets and posters distributed around Rome. Communication in today’s organizations is frequently discussed, but not always delivered. The suggestion that leaders meet with their people on a regular basis is often greeted with the response that there is not enough time. But such meetings provide valuable opportunities to share information, layout the work, anticipate problems, and gather momentum. They also reinforce a sense of cooperative helpfulness and mutual support. Meetings can serve as an opportunity to close the communication loop and see if frontline people are receiving information and hearing the leader’s message.

- Support (providing guidance). Even in routine situations, when there is no emergency or strategic crisis, people benefit from support in the form of feedback. As a rule, they do not get enough of it. One can ask people in almost any organization, "How do you know if you are doing a good job?" Ninety percent are likely to respond, "If I do something wrong, I'll hear about it." Too often, this topic is discussed as if praise were the only answer; it is not. What people are saying is that they do not have sufficient discussion about their performance and tangible support from their leaders to improve effectiveness. Successful leaders know that praise without support is an empty gesture.

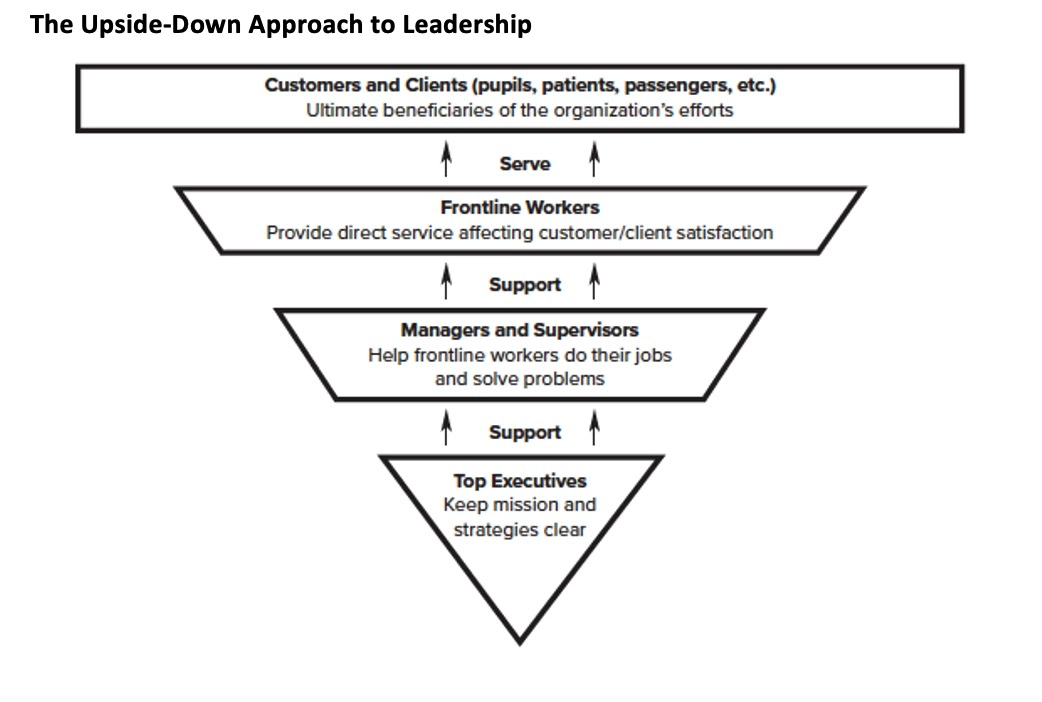

A picture can be an excellent way to convey a concept. The servant-leader uses the upside-down pyramid approach to leadership. See the figure below.

Leadership author Ken Blanchard states that you become a servant leader when you believe you are here to give rather than get; you're here to serve, not to be served. Servant leadership encourages trust, listening, and the ethical use of power and empowerment.

Frontline workers are at the top of the pyramid. They are supported in their efforts by leaders below them. The implications are dramatic for day-to-day work. From this perspective, each person provides added value. The whole organization is devoted to satisfying the customer, and this is made possible through the support of caring leaders.

The founding philosophy of Marriott International is based on the upside-down pyramid approach to leadership, traced to the words of J.W. Marriott: "Take care of the associates, the associates will take care of the guests, and the guests will come back again and again." When senior leaders serve managers and supervisors, and managers and supervisors serve frontline employees, the focus of employees is on serving the customers. Such organizations in the private sector thrive and grow. Such organizations in the government and nonprofit sectors fulfill the public trust.

Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts is an upside-down pyramid organization. It's 1 of only 12 companies to be ranked in the "100 best companies to work for" every year since Fortune magazine started its annual ranking of companies. Founder Isadore Sharp states, "How you treat your employees is how they will treat the customers. Our culture has always been based on the Golden Rule -- the simple idea of treating others as you would have them treat you." The upside-down pyramid approach of servant leadership leads to greater customer focus, employee satisfaction, and company success.

When Fortune announced its list of great leaders, the top spot was awarded to Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Distilled from Jeffrey Krames's book Lead with Humility, five lessons stand out: be humble, admit mistakes, go where you are needed, serve others, and persevere. Pope Francis clearly understands that leaders serve people, not institutions.11

Max DePree, in his book Leadership Is an Art, describes the character of servant leadership:

The first responsibility of a leader is to define what can be. The last is to say thank you. In between the two, the leader must become a servant and a debtor. That sums up the progress of an artful leader.

In a day when so much energy seems to be spent on maintenance and manuals, on bureaucracy and meaningless quantification, to be a leader is to enjoy the special privileges of complexity, of ambiguity, of diversity. But to be a leader means, especially, having the opportunity to make a meaningful difference in the lives of those who permit leaders to lead.12

As CEO of the furniture manufacturer Herman Miller, Depree wrote about his own work environment: I would like my office to encourage openness and contact with other people; not a country club atmosphere, but a place where there is good performance and work gets done in a warm and friendly way.

Successful leaders know that 80 percent of the work is typically done by frontline employees. Walt Bettinger, CEO of Charles Schwab, tells a servant leadership lesson that has stayed with him: I had maintained a 4.0 average all the way through a business strategy course in my senior year. The professor handed out the final exam on one piece of paper with both sides blank. The professor said, I have taught you everything you need to know about business, except the most important message. The question is this: What is the name of the lady who cleans this building? This had a powerful impact. It was the only test I ever failed, and I got the B I deserved. Her name was Dottie, and I didn’t know Dottie. I’ve tried to know every Dottie I’ve worked with ever since. It reminded me of what really matters in life, and leaders must never lose sight of the people who do the real work.13

Questions for Discussion:

- Can you think of a leader or professor who embodies servant leadership?

- Do you as a leader or professor fulfill this role?

- What do you do to ensure access, communication, and support to help others achieve their full potential to learn, work, and grow?

- R. Greenleaf, Servant Leadership (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2002); and R. Greenleaf, The Servant as Leader (Newton Centre, MA: Robert K. Greenleaf Center, 1970).

- L. Spears and M. Lawrence, eds., Focus on Leadership (New York: Wiley, 2002).

- H. Hesse, The Journey to the East (New York: Noonday, 1968); see also L. Bolman and T. Deal, Leading with Soul (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011).

- H. Levinson and C. Lang, Executive (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), pp. 187ñ89.

- L. Spears, "Practicing Servant Leadership," Leaders to Leaders 34 (Fall 2004); and "2006 Movers and Shakers," Financial Planning ≠(January 2006), p. 1.

- Q. Studer, Hard Wiring Excellence (Gulf Breeze, FL: Five Star Publications, 2005); and Q. Studer, Results That Last (New York: Wiley, 2007).

- A Bryant, Quick and Nimble (New York: Times Books, 2014); and L. Bock, Work Rules! (New York: Twelve Publishing, 2015).

- M. Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2006); and E. Hallowell, "The Human Moment at Work," Harvard Business Review 77, no. 1 (January- February 1999), pp. 58ñ65.

- L. Gallagher, "Why Employees Love Marriott," Fortune (March 15, 2015), pp. 112ñ18; and J. Hunter, The Servant (New York: Crown Business, 1998).

- D. Jones, "Does Servant Leadership Lead to Greater Customer Focus and Employee Satisfaction?" Business Studies Journal 4 (2012), pp. 21ñ23 ; M. Moskowitz and R. Levering, "The 100 Best Companies to Work For," Fortune (March 5, 2015), pp. 140ñ54; and I. Sharp, Four Seasons (New York: Portfolio, 2012).

- J. Krames, Lead with Humility (New York: AMACOM, 2014).

- M. DePree, Leadership Is an Art (New York: Crown Business, 2004), pp. 45ñ53.

- A. Bryant, "Walt Bettinger of Charles Schwab: You've Got to Open Up to Move Up," The New York Times (February 4, 2016).