Coping with Change: The Importance of Attitude

The only constant in life is change. The right attitude can make navigating change more manageable and inspiring rather than overwhelming.

"It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change". - Charles Darwin

Nearly 2,500 years ago, the Greek philosopher Heraclitus noted that we can never cross the same river twice. In other words, change is a constant in life. The volume, speed, and complexity of change are increasing in modern times. In our personal lives, we are constantly having to adjust to family, job, and health changes. In society at large, we face escalating changes in government, education, religion, and other institutions.1

People are acutely aware of change in their lives, and many have difficulty adjusting. Among the causes of change are a growing worldwide population, faster communication, greater access to information, increasing technological advancements, and the breakdown of traditional rules and social order.

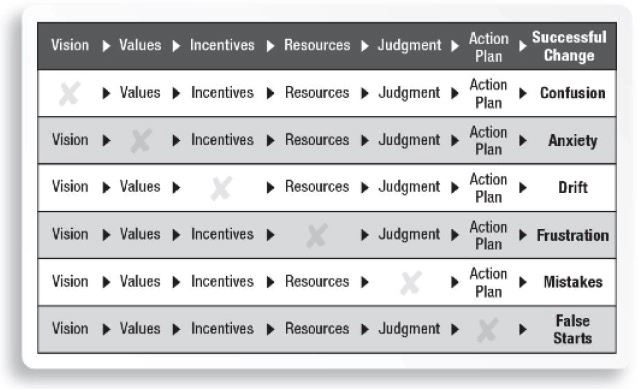

Managing change successfully requires building blocks: 1) a focused vision, 2) guiding values, 3) personal incentives, 4) supporting resources, 5) sound judgment, and 6) an action plan. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Building Blocks for Successful Change2

Without a vision or clear goals, there is confusion. Without values, there are no standards of right or wrong and anxiety results. Without incentives, there is a lack of energy, and the individual drifts as the pawn of external forces. Without resources, there is a lack of progress, and frustration is experienced. Without judgment, poor choices are made, and mistakes occur. Without an action plan and strategy for change, there are false starts.

In dealing with personal change, use this model and ask yourself these questions:

- Do I have a clear, compelling vision and a purpose in life with meaningful goals to achieve?

- Do I have values and principles that anchor and guide me?

- Do I have incentives and motivation to take responsibility for my own destiny?

- What resources can I garner to achieve my goals?

- Do I balance feelings with logic and let reason guide me so that my judgments are sound?

- What plan of action should I follow and what steps should I take for successful change?

In all walks and periods of life, we are faced with the challenge of change. To the building blocks of vision, values, incentives, resources, judgment, and an action plan, add two essential elements: the will to change and personal courage. In the final analysis, the ability to change is less a function of capacity and more a function of determination and courage to live by one’s convictions in the face of adversity.

Helping People Through Change

Change is the label under which we put all of the things that we have to do differently in the future. In general, people dislike change. It makes a blank space of uncertainty between what is and what might be. This is especially true for older men.

Psychologist Kurt Lewin identified a three-step process for helping people through change. The steps apply in all change initiatives—parents in the home, managers on the job, and leaders in the community. First, unfreeze the status quo. Second, move to the desired state. Third, live by conditions that become the new, but not rigid, status quo.3

- Unfreezing involves reducing resistance to change. To accept change, people must resolve feelings about letting go of the old. Only after they have dealt successfully with endings are they ready to make transitions.

- Moving to the desired state involves considerable effort. Discussion, brainstorming and research are good techniques for channeling energies. One of the best ways to implement change is to involve people in changes that will affect them.

- Living by new conditions involves pointing out successes and rewarding people involved in implementing the change. This increases willingness to participate in future change efforts.

Transitions author William Bridges describes Lewin’s three-step process as letting go of the way things used to be and taking hold of the way they subsequently become, with a neutral zone in-between when tremendous insight and growth can occur. The transition can be reactive, such as after personal loss, or developmental, such as recognition of alternatives to the status quo.

Myths and Realities in Dealing with Change

Historians have identified ages or periods of history—the Dark Ages, the Renaissance, the Age of Reason, and so on. An argument can be made that the current period is the Age of Change. In one way or another, people have always had to deal with change—from social change to change in technology. What is different today is the volume and speed of change and the diminishing effectiveness of our responses.4

There are a number of myths and realities in dealing with change. One myth is that change will go away when the reality is that change is here to stay. If you have lived long enough, you have witnessed firsthand the truth of this statement as you have seen your own body change, family change, work change, and even your mind change.

Another common myth is that I can just keep on doing things the way I have been when the reality is if your world is changing—home, work, and society—then you may have to change as well. For example, if the marketplace, technology, or other external forces require working differently, can we as individuals expect to succeed if we are unwilling to make adjustments? Sometimes, in order to protect family, health, and other high-priority values, people have to make changes.

The Importance of Attitude

What a person does when change occurs depends upon his or her attitude. At one extreme, the individual may shut down and declare, “I will never change.” A more effective approach is to keep an open mind and say, “Let’s consider the possibilities.”

In all areas of life, attitude affects our happiness, effectiveness, and general well-being. Attitude can make or break your career, your relationships, and even your health. We have all known someone with an attitude problem.

Some people take the attitude of the victim when change occurs. This robs them of personal energy and makes them less appealing to others. In contrast, other people view change as a challenge and focus on the opportunities and benefits that change can bring.

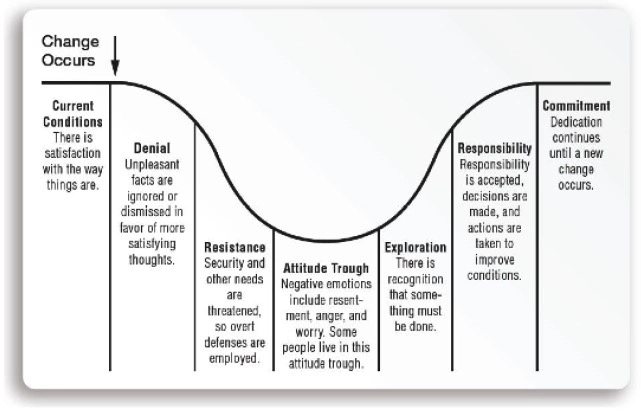

The power of attitude to change people’s lives is reflected in the statement, “If you change your attitude, your attitude will change you.” Figure 2 shows an attitude curve in response to change.

Figure 2: Attitude Curve in Response to Change5

The following is a description of each phase of the attitude curve:

Current Conditions. Conditions are the way one likes them. There is a feeling of satisfaction and well-being. Events appear stable and manageable.

Change Occurs. Caused by self or caused by others, something changes. On the job, in the home, or in society at large, change occurs that impacts the person.

Denial. Unpleasant facts and circumstances are mentally and emotionally denied. Avoidance behavior is shown and silence is evident as people don’t want to face the reality of change. People don’t want to know about, talk about, or otherwise deal with change in their lives.

Resistance. The fact is accepted that a change has occurred, but resistance develops as personal needs are threatened. Resistance is intensified if the change is seen as unnecessary or if people don’t like the way it is introduced. During the resistance, forces are garnered to combat change. Energy is dissipated and people have difficulty concentrating, as they complain about conditions and yearn for the past.

Attitude Trough. Negative emotions are experienced, including resentment, anger, and worry, as well as fear and guilt. Joy and enthusiasm are missing. There is a loss of vitality and a feeling of resignation. Physical and emotional signs of stress are common. Some people live their lives in this attitude trough.

Exploration. When conditions are intolerable, the exploration begins. The individual goes from a closed and defensive state to a condition of awareness. Alternative ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving are considered. There is new interest and a sense of hope for the future.

Responsibility. Personal responsibility is accepted to improve conditions. Decisions are made and acted upon. Energy builds as the individual takes control of his or her own life. There is a coordinated effort and a feeling of enthusiasm. Creativity characterizes behavior.

Commitment. The highest level of the attitude curve is achieved. It is characterized by a sense of purpose, emotional strength, and personal mastery. There is an overall feeling of satisfaction and well-being. You see high performance and personal pride.

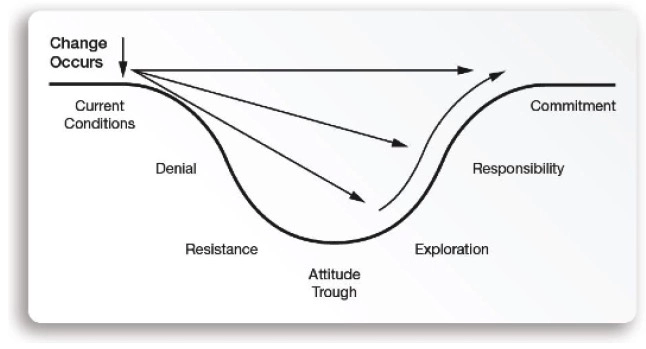

Figure 3 shows effective responses in dealing with change. Denial, resistance, and negative attitudes are avoided in favor of proceeding directly to states of exploration, personal responsibility, and commitment. This is most likely to happen when people:

- Believe change is the right thing to do

- Have influence on the nature and process of change

- Respect the person who is championing the change

- Expect the change will result in personal gain

- Believe this is the right time for change6

Figure 3: Effective Response in Dealing with Change

In coping with change, the most important factor is the degree to which people possess resilience—the capacity to absorb high levels of change while displaying minimal dysfunctional behavior. Another term is hardiness, based on the characteristics of personal commitment, sense of control, positive attitude, balanced perspective, and caring relationships. Hardy people face no less of a challenge than others when confronting a crisis or experiencing a loss, and their sorrow is no less, but they have the capacity to maintain effective behavior that is necessary to preserve physical and emotional health. See the blog post—Adaptive Capacity: Achieving Success and Living to Tell About It.

Initiating Change

Thus far, our discussion about change has dealt with reacting healthfully and effectively to a changing world. What about initiating change? What if one’s goal is to change others or improve conditions? This is an admirable ambition, but a word of advice from an old and wise source is worth remembering.7

It Starts With You

When I was young and free, and my imagination had no limits I dreamed of changing the world. As I grew older and wiser, I discovered the world would not change, so I shortened my sights somewhat and decided to change only my country.

But it, too, seemed immovable.

As I grew into my twilight years, in one last desperate attempt, I settled for changing only my family, those closest to me, but alas, they would have none of it.

And now as I lie on my deathbed, I suddenly realize: if I had only changed myself first, then by example I would have changed my family.

From their inspiration and encouragement, I would then have been able to better my country and, who knows, I may have even changed the world. - Bishop, name unknown, Westminster Abbey, 1100 A.D.

More modern but similar advice on this question is provided by the Indian political and spiritual leader Mahatma Mohandas Gandhi, who said the following: “If you would change the world, you must be the way you want the world to be.”

- Conner, D.R. (1993). Managing at the Speed of Change, New York, NY: Villand Books.

- William Stavropolus, CEO, The Dow Chemical Company, 1997.

- Lewin, K. (1935). A dynamic theory of personality. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Conner, D.R. (1998). Leading at the Edge of Chaos. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Scott, C.D. & Jaffe, D.T. (1998). Managing organizational change: A practical guide for managers. Los Altos, CA: Crisp Publications.

- de Bonvoisin, A. (2009). The first 30 days: Your guide to making any change easier. New York, NY: HarperOne.

- Canfield, J. & Hansen, M. (1993). Chicken soup for the soul: 101 stories to open the heart and rekindle the spirit. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.