Do My Students Understand What I’m Saying?

Find tips and new ways to communicate with students to make sure everyone's on the same page and they're getting the most out of class.

A little bit of kindness has not hurt anyone.

Everyone thinks they have great communication skills. After all, we’re educators. We know how to explain our subject material and how to speak with students – we do it nearly every day as a career!

But the real question we should all ask ourselves is what do our students actually see and hear when we talk to them? Are we truly coming across as intended or are our students getting an incorrect, filtered version? Is the perception of our communication style hindering what we’re trying to teach?

Even the best communicators and educators amongst us can always consider a few helpful tips to make their message clearer:

Large Group Communication

A vast amount of your communication to students will actually be to the class at large. There are a couple of things to keep in mind:

- Reminders. May instructors use Remind to send students updates and reminders about due dates, assignments, tests, etc. This can be one of the most effective ways to communicate with large groups of students easily and quickly.

- Group emails are another great quick and easy way to communicate with students while retaining official records of such communication.

Some of the common-sense rules for group communication are:

- Bcc if e-mailing multiple students

- Always use college-assigned e-mail addresses for students. Suggest that the students either link their school and personal accounts or forward their school e-mail to their personal accounts.

- Always use college assigned instructor e-mail address

Best email practices to support your classroom instruction:

- Introduction e-mails before the start of the semester might include details about the classroom, course materials, and brief instructor information.

- Additional explanations and instructions. I frequently use “tickets out of the door” to survey students’ grasp of the lesson material. If students’ responses show uncertainty, confusion, or misunderstanding of the instruction or some of the information we discussed in class, I can send a quick re-teach e-mail to save time in class.

- Lesson follow-ups. During the class discussions, brainstorm sessions, various activities, I capture the information in Word and project it on the board. At the end of class, I save the class notes and e-mail them to students right away. Not only do my students have notes to review and to study, but those who miss the class can also be caught up, and I maintain compliance with ADA accommodations if I have students who need those.

- LMS emails and announcements. Learning Management Systems (on-line platforms used to teach distance learning courses) are another alternative to communicate with students. One catch, however, is to make sure that students check their school e-mails and log into LMS regularly. This communication medium works best for online and hybrid classes.

Individual or 1:1 Communication

There are different reasons why an instructor might want to contact individual students. In these cases, it’s best to reach out to these students individually by either email or after class:

- Check on students who were not in class

- Praise students who did an outstanding job in class

- Encourage reluctant learners

- Discuss specific student work, such as essays, tests or exams, projects, grades, etc.

- Address any issues with academic honesty or plagiarism

Communication Language and Tone

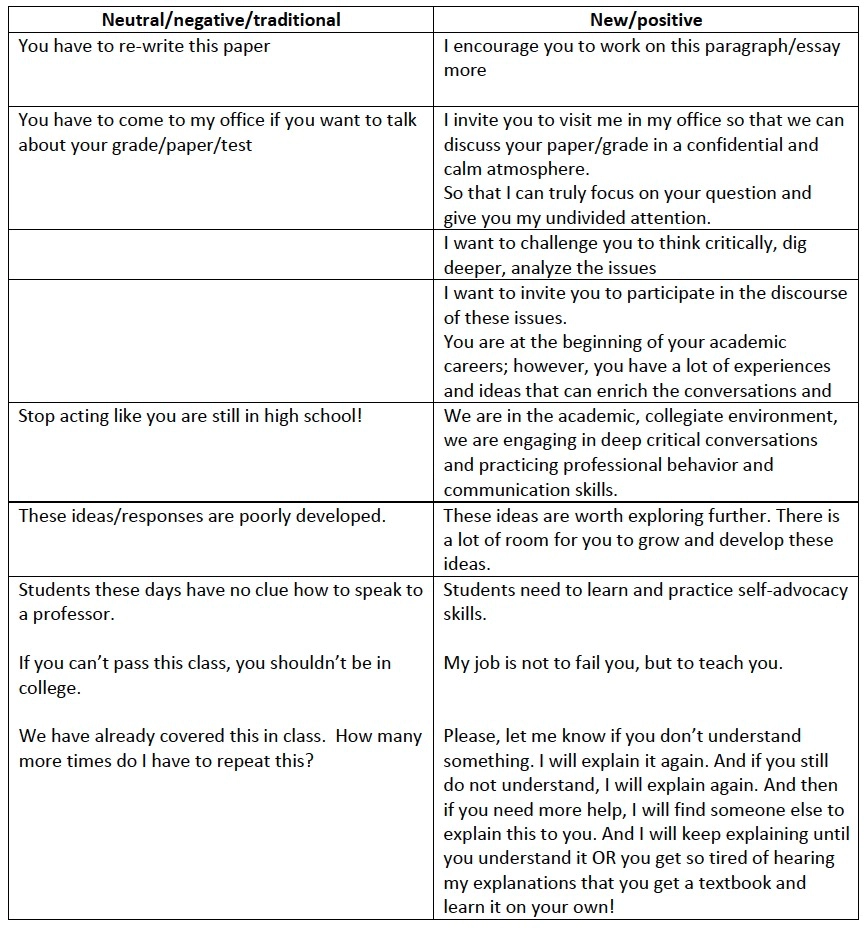

How you phrase something can be almost as important as what you say. Many times, students can perceive feedback as criticism and think instructors are unjustly “picking on them”. One of the best ways to mitigate this is to consider negative vs positive language choices:

Responding to Parents and Significant Others

Students are adults (mostly). We shouldn’t have to hear from their parents, right?! While that’s true, the reality is you might be contacted by anxious, curious, or helicopter-y parents and significant others. It’s important to consider some key communication rules with them:

- Privacy laws. Students enrolled in college are legally considered adults and as such are protected by privacy laws. Each faculty member should be familiar with FERPA and the school’s privacy policies. However, situations arise when a parent or a significant other contacts an instructor on behalf of a student.

- Standard Response. A faculty member cannot discuss any information without making sure that there is a FERPA release on file for that particular student. The verification of this information can take some time. There are ways a faculty member can respond without violating FERPA regulations and yet not escalating the situation. Here is a possible way to respond:

“Dear [Name], thank you very much for contacting me on behalf of your [son/daughter/spouse]. It is important that all college students have a strong support system at home. I wish more students had strong advocates at home. As much as I want to provide immediate assistance or answer your questions, I am obligated by law to maintain confidentiality. Please, encourage your student/son/daughter/spouse to contact his/her instructor(s) directly; in the meantime, I will check to see if the school has a FERPA on file.”

There are no one-size-fits-all scenarios and situations in life. Every day, every class, every contact with students presents a new challenge or requires a new approach. As instructors, we often feel the pressure of being tough, setting high expectations, and sticking to our guns. I entreat all those passionate about helping students, educating students, supporting students to start with kindness and compassion when choosing what we say and how we say it. Our students are not only learning math, science, composition, but what it means to be professional, to be a productive member of society, and to be an effective communicator. Do we want to chastise, demand, and criticize? Or do we want to encourage, inspire, and educate?